I don't quote my own blog posts very often, but a recent article in Slate, "

Facebook wants to know why you didn’t publish that status update you started writing," spotlights an issue that caught my attention in the earliest hours of the Snowden revelations. It's prompted some discussions and then some advice that's worth a post of its own, so here goes.

Some of Snowden's first bombshells included disclosures that US and allied intel agents could monitor users' logins and other activity on the Internet in real time even for encrypted services. In the aftermath of these leaks, I commented,

The "As-You-Type" claim is a special concern

Webmail services help prevent loss of your work in the event of a disconnect or crash by frequently storing your draft on their server as you compose it. This blog post, for example, has been saved to Blogger's server automatically many dozens of times as I've worked on it. Had I typed something incendiary and intemperate about some politician or bureaucrat, that would have been stored as well-- and potentially monitored and inspected if my phrasing (or integrated profile) contained certain keywords or triggers. This means cloud-based services of a wide variety have the capability of capturing and potentially monitoring your evolving thoughts and phrasing, even if you think better of them before committing the "Send" or "Publish" button. So, it's bad enough that what you email and say is monitor-able... what you think is also.

So the automatic server-saving of your drafts not only provides crash-proofness but allows the service you’re using (and any eavesdroppers, hm?) to observe your thought processes and note any evanescent notions that you may have reconsidered and deleted. Creepy much?

Five essential tools for maximizing privacy

In response to that article, a correspondent asks if his privacy is more assured if he does his drafting in a word-processor on his computer instead.

Well, as should be clear by now, if your drafts are on some server somewhere, they can in theory be accessed and reviewed by corporate or governmental authorities. It's happened:

just ask David Petraeus. So you might expect that if your drafting and deletions are entirely constrained to files on your local disk then they would remain private. Unfortunately it's not quite as simple as that in today's connected world.

Basically: your drafts are private if they're on your computer and not benefiting from any sort of cloud storage or backup service, and assuming no entity has installed a key logger or other monitoring tool on your computer, and that no one physically or remotely accesses your machine while your drafts are on it in some accessible form ...which might not be at all obvious.

That last point is an interesting one. I've lost the citation but recall how some guy was convicted for some terror-related crime in the past couple years based in part on evidence collected from

scratch files scattered on his disk by his word processor. Finding this evidence was possible because he had not encrypted his hard disk, allowing easy forensic analysis of his activities. The only defense against this sort of forensic analysis (whether by government or other entity) is to encrypt your disk with a strong password; in the US at least there are legal obstacles to forcing you to give your password up even if accused of a crime. (Biometric authentication is

not constitutionally protected. So if Fifth Amendment protections against self-incrimination are important in your situation, know that anything protected by something like a fingerprint sensor can be opened by the authorities if you're accused of a crime.)

So there are nuances to what one might expect to be a simple answer. Meanwhile, the only real news in the Slate article referenced above is that stuff you delete from a hosted draft may still have been noted and logged. And frankly, that shouldn't be news to alert readers by now.

The first essential tool: personal encryption

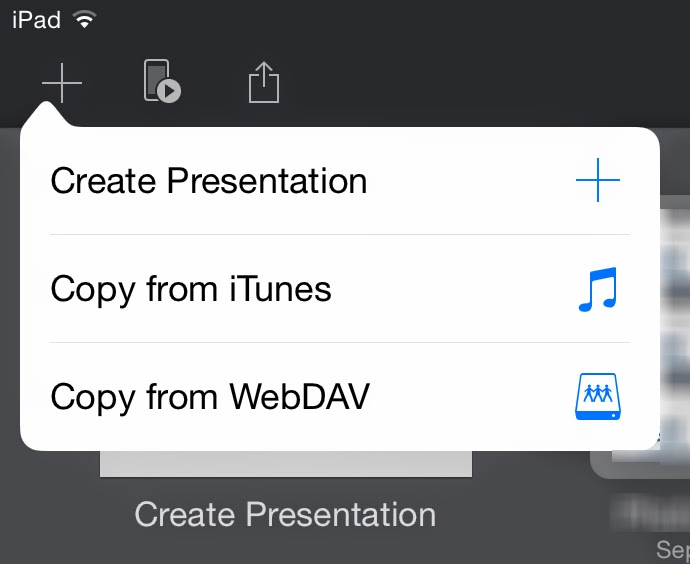

Let's face it, cloud services are popular because they're useful. For example, I routinely do my work in files stored in my Dropbox folder. The benefit to me is that I can access them from anywhere using any of my devices or even a browser on someone else's machine. This has been very beneficial to me, plus Dropbox keeps versioned backups of my files, so if I whoops something it's easy to return to a previous version. Dropbox is a wonderful, reliable, non-creepy, secure service I

recommend highly and for which I have documented ways to

virtually assure the privacy of your files. (Newer, self-hosted services like

OwnCloud or

Bittorrent Sync provide capability similar to Dropbox's without third-party involvement, leaving only the transport channel and physical or remote access to one's machines as potential vulnerabilities.)

Of course, were I writing some sort of radical manifesto, keeping my drafts in my Dropbox might not be the best approach for staying under the radar. Snowden's whistleblowing tells us that agencies of governments friendly and otherwise (and, who knows, some well-resourced corporations or other entities) now regard ordinary encryption as opaque as Saran Wrap. Though I'm not in the habit of writing manifestos or possessing other dodgy files, there are some aspects of my finances and work where confidentiality is important, and in those situations I perform my own duplicative private encryption, which is less likely to be easily cracked.

So, the first tools to acquire and learn to use are personal encryption utilities. For those lucky enough to be using a Mac,

OS X's built-in ability to create bandwidth-friendly encrypted sparsebundle disk images is a boon. A helpful reader points out

EncFS as another effective, cross-platform tool for bandwidth-conserving file encryption. For any platform,

TrueCrypt provides good capabilities for encrypting files and creating encrypted disk images, although it lacks the sparsebundle capability that's so beneficial for online storage situations.

For me, the benefits of using online services the way I use them outweighs the risks, which I've reduced and mitigated through tools such as these. Similarly, I use gmail for some of my e-correspondence. It's a great service. I recognize that I, the user, am the product, and the service markets me to its customers as a digital dossier collected from my activities, connections, communications and (per the Slate article) thoughts. Of course, anyone who writes to me c/o my gmail account gets databased, too... an example of how our personal privacy decisions have implications extending beyond the penumbra of our individuality.

The second essential tool: Whole-disk encryption, and password-enable your device

As previously related, I once caught a coworker just as he started poking around on my laptop after he thought I'd left the office. He was an odd sort of duck, and my immediate thought was that he intended to put something problematic on my machine. It happens. In fact, it's the sort of threat that's far more likely than NSA targeting most readers here.

And it's readily addressable: turn on your device's password capabilities, including a screen-saver password or other lock-code that activates when your machine is unattended. This goes for your smartphone as well as your computer.

But this is just an inconvenience to a determined attacker. Devices get lost or stolen all the time, and Evil Hotel Maids in some countries can and do access computers left in visitors' rooms to perform espionage on behalf of some state or industrial entity. The best defense against this is a good whole-disk encryption scheme. For example, the Mac's

FileVault 2 option has been a standard feature of OS X for several generations now, and it is highly effective and

efficient. If your machine's manufacturer offers something of the sort, turn it on. If not, read some reviews and buy a utility that will do the job.

iPhones and iPads automatically encrypt their file systems when a passcode is turned on-- brilliant. So, do that. Recent versions of Android offer something similar.

The third essential tool: Email encryption

Ed Snowden insisted on PGP encryption of email communications, and that's a remarkable endorsement of this free and effective technology. Its developer, Phil Zimmermann, nearly went to prison for developing it, and

then-Sen. Joe Biden made two attempts to sneak wording criminalizing personal encryption into totally unrelated legislation. It's instructive to ponder why tools that allow individuals to maximize their own privacy have been so controversial for so long... this occurred more than a decade before 9/11.

Today, much of what we do on the Internet is encrypted in transit from your computer to at least the first node in the chain to whatever service you're using. But that only means eavesdropping is blocked to those lacking the keys, and only while in transit, and only for that hop. For example, Gmail is very securely handled between your browser and the Gmail servers. Once there, your emails are stored in plain text.

Worse:

Under the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA) of 1986, police only need a subpoena, issued without a judge's approval, to read emails that have been opened or that are more than 180 days old.

Meanwhile, the repeated compromises of the public Certificate Authorities suggests any encryption based on CA-managed keys may be vulnerable.

The solution is to heed Snowden's advice and manage your own email encryption for those situations when postcard-class privacy is inadequate.

Setting up PGP takes a little effort and is, unfortunately, still a bit of a geek-fest, but it's worth the effort. Mac users have it especially easy via the marvelous

GPGTools.org toolkit, which integrates brilliantly with Mac's Mail.app.

GPG4Win offers something similar for Windows users. And all participants in a conversation must have established and exchanged their public keys. Assuming the participants are trustworthy and careful, this ensures that private discussions remain private.

The fourth essential tool: Back up!

We tend to get worked up about the risks to our data, wealth and privacy from shadowy agencies and sinister corporations, but the greatest risk is the most unavoidable: the eventual failure of our disk drives, including SSDs. That is a matter of when, not if.

There's only one defense, and that is to maintain current and duplicative backups. Invest in two USB pocket drives, and back up to them in alternating fashion. Keep them in different places. And consider supplementing your local backup strategy with online backup services like Carbonite or my own chosen service,

Backblaze. All offer excellent transport encryption; Backblaze offers a free additional private-encryption capability which further cloaks your stuff on their servers, for a great price.

But if the service happens to back up a draft that you're working on, then there's another example of your drafting-and-deletions hypothetically being accessible to someone with the right access and tools. But that's many levels lower in terms of exposure than writing your drafts in a gmail/Yahoo/Hotmail composition window, Facebook draft post, Google Docs draft, etc.

The most essential tool: control your own computer

So there are things you can do to improve privacy and increase the chances of flying under the radar of governmental and corporate eavesdroppers and snoops. Short of staying offline entirely, that can include

- Carefully selecting (and minimizing) what online services you use and how you use them,

- Choosing an operating system that is comparatively secure,

- Employing disk, file and transport encryption to increase security, and

- Leveraging virtualization, compartmentalization, userspace separations and utilization of separate machines.

That last recommendation is quite important. We tend to fixate on the shadowy cloak-and-dagger players, and sure: those are sexy threats that make headlines. But the likelihood most of us will be snared by their tentacles in any meaningful way are small compared to the potential consequences of other dumb things we do.

Top among them: using your company computer for personal purposes.

Just don't.

For starters, it's a great way to get fired. I've known smart people whose work is legally quite sensitive yet they watch naughty videos, play online games, download warez and do other risky things on their company computers, sometimes even in their normal user accounts. Dumb, dumb, dumb.

Just ask John Deutch. (What is it about CIA Directors and their digital idiocy?) Frankly, if I caught an employee doing that, I'd fire 'em myself just out of intolerance for dumbasses.

So, just don't. With the cost of terminating employees growing higher every year, IT departments are increasingly tasked with monitoring employee computer usage, documenting offenses useful for knocking down exit demands and defending against termination-related lawsuits. So keyloggers are routinely installed, screen-snaps are covertly acquired, webcams are snapshotted to capture employee behavior, networking logs are databased... do a bit of searching and you'll find many super-creepy examples out there of employers watching and observing everything their employees and contractors do at the keyboard, and of tools marketed to them for ever deeper surveillance, tools like

http://talygen.com/CaptureScreenShot and

http://www.oleansoft.com --there are dozens and dozens.

That is a far more present threat to most people than the NSA, or industrial espionage, or the depredations of sneaky social-networking services and ad-platform companies masquerading as cloud service providers. Solution: Get your own damn laptop or tablet, and lock it down, and keep it in your possession as much as possible, especially when you travel.

And mind your assumptions. If you think you're safe, you're doing it wrong.